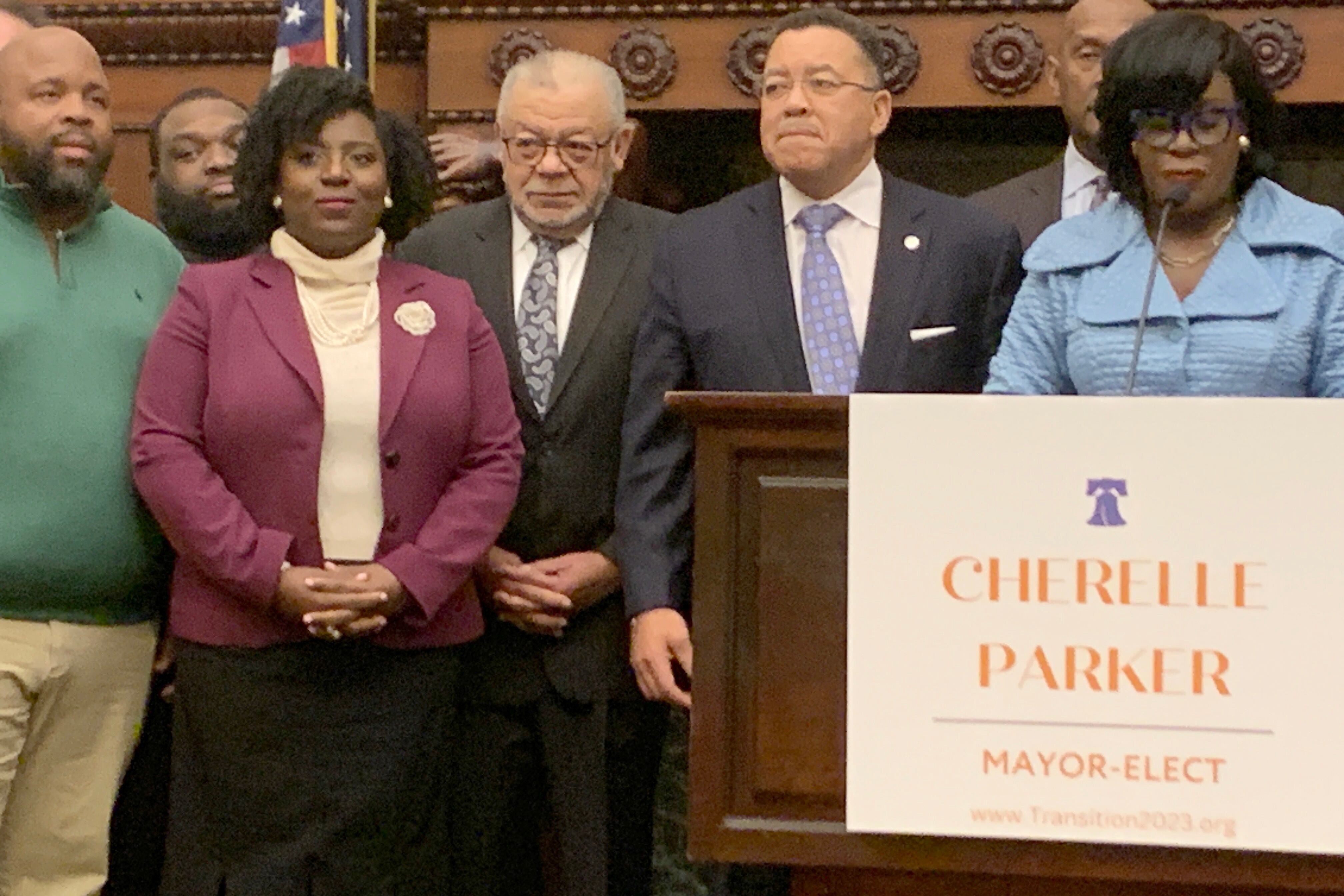

Mayor-elect Cherelle Parker has named Kevin Bethel, the School District of Philadelphia’s current chief of school safety, as her new police commissioner.

Bethel has long been a well-respected fixture in Philadelphia law enforcement and school safety circles. During his tenure in the school district, Bethel focused on reforming the juvenile justice system, dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline, and promoting “trauma-informed policing.”

As a deputy police commissioner and then the district’s safety director, he also developed a national reputation for his work emphasizing prevention over punishment as an approach to improving student behavior and discipline both in and out of school settings.

In his four years leading school safety for the district, “I believe we have made the schools safer,” Bethel said at his appointment announcement at City Hall on Wednesday. “It’s unacceptable that some students feel unsafe going to and from school.”

This is Parker’s first mayoral staffing announcement, though she doesn’t officially take office until January. She said that she chose Bethel from among three candidates chosen by a search committee headed by former police commissioner Charles Ramsay.

Deputy Chief of School Safety Craig Johnson will serve as interim chief for the district while a search is conducted for Bethel’s replacement, according to the district.

“Chief Bethel is a class act, and I always felt very confident knowing that he was overseeing all efforts to create safe learning environments for our students to imagine and realize any future they desire,” Philadelphia Superintendent Tony Watlington said in a statement Wednesday.

The Board of Education issued a joint statement calling Bethel’s appointment “well deserved” and that his departure would be a “significant loss” for the district.

Bethel’s school safety legacy in Philadelphia schools

A John Bartram High School graduate, Bethel’s oft-repeated motto during his time in the police department and school district has been: “I didn’t become a cop to lock up children.”

While on the police force in 2013, Bethel said he was “alarmed” by how many students were being arrested in the city under a “zero tolerance” policy that saw police called on students as young as 10 years old.

“I can’t lock up a 10-year-old child who comes to school with scissors,” he said.

He described his dismay at a school in Kensington that put bulletproof blankets on the windows due to nearby shootings.

“I lived it when kids have been shot in front of our schools,” he also recalled. “I never thought I would take a job where kids would be killed at the doorstep of a school.”

With buy-in from district officials and others, Bethel created a diversion program for students with no prior delinquency record who committed low-level offenses like fighting or possessing a pocket knife. That program was praised at the time for substantially decreasing the number of students arrested in school from nearly 1,600 in 2013-14 to 251 in 2018-19.

Bethel has also worked to improve the district’s weapons detection process — a pain point that’s drawn public fury.

In 2019, outraged protesters shut down a Philadelphia Board of Education meeting after members voted to make metal detectors mandatory in every district high school. In the years after, random wand screenings, X-ray machines, and other detection systems have been used in high schools and some middle schools.

Some parents and community members have been critical of the practices, which they said can make students feel criminalized in their own schools.

When he announced new school safety measures last August, Bethel said the district would be introducing a new “minimally invasive gun detection system” in 14 middle schools. Those detectors were chosen because district officials were looking for technology “that did not add to the trauma of our young people,” Bethel said at the time.

To be sure, the city still struggles with youth incarceration issues. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported in June that the city’s juvenile detention center reached its highest population levels ever, with 230 young people in custody. The Inquirer discovered overcrowding resulted in dozens of young people forced to sleep in offices, gyms, or on the floors of “filthy” cells.

As commissioner, Bethel said Wednesday he would work to make police officers a vital part of communities, not just enforcers of the law.

“I’m proud to be a cop,” he said. “We’re not your enemy. We’re here to serve, and I ask you to give us that opportunity to do that. … Raise your voice when it needs to be raised, but let’s be part of the community, let’s work with you.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.

Carly Sitrin is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Philadelphia. Contact Carly at csitrin@chalkbeat.org.